Back to Square One? Natural vs Lab Grown Diamonds

For more than a decade, the diamond industry has been moving towards what many believed was a position of relative certainty. The distinction between natural and lab grown diamonds had become technologically robust, commercially embedded and, crucially, widely trusted. Advanced spectroscopy, growth structure analysis and luminescence mapping were thought to have closed the chapter on ambiguity. Yet recent observations surrounding unexpected UV afterglow behaviour in natural diamonds, serious enough to prompt renewed scrutiny from the Gemological Institute of America, suggest that the narrative may be far from settled. The question now circulating across laboratories, trading floors and auction houses is uncomfortable but unavoidable. Are we being forced to start again from first principles?

When a Diagnostic Shortcut Becomes Doctrine

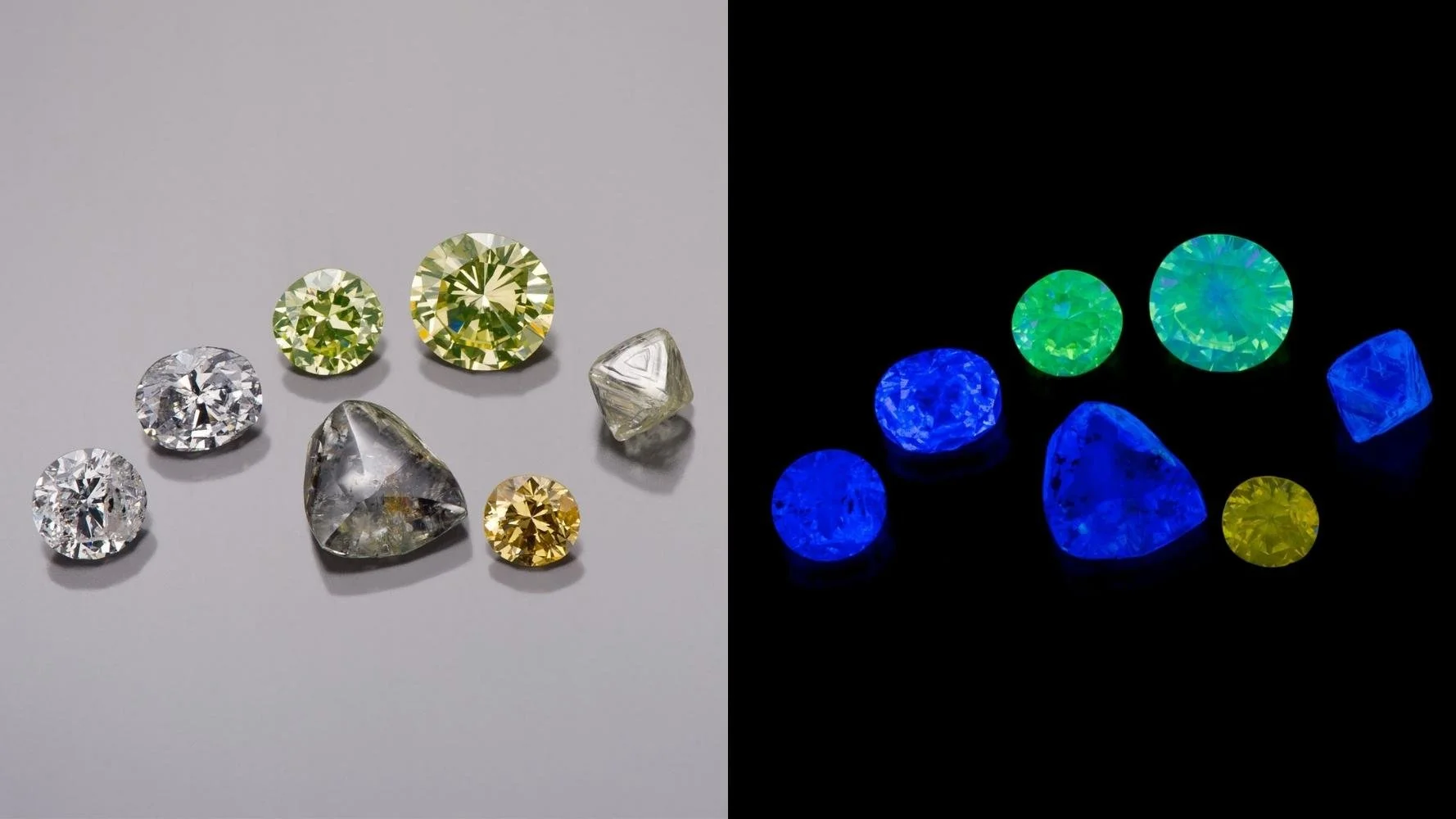

The issue emerges from reports of natural diamonds displaying prolonged ultraviolet afterglow, a reaction long considered a hallmark of certain lab grown stones, particularly those produced via chemical vapour deposition. Historically, persistent phosphorescence under UV light has been associated with defects linked to laboratory growth environments, especially boron-related structures in synthetic diamonds. This diagnostic shortcut became deeply ingrained in screening processes, from rapid trade-level testing to advanced laboratory workflows. The assumption was simple. Strong afterglow equalled lab grown. Natural diamonds, while capable of fluorescence, were not expected to behave in the same way.

That assumption is now being challenged.

Why These Diamonds Matter

The diamonds under examination are not marginal stones of questionable provenance. They are reportedly natural, accompanied by established documentation and mined from known geological sources. Their unexpected behaviour under UV light has been sufficient to raise internal flags at GIA, not because of immediate doubts over origin, but because it disrupts a classification logic that has underpinned the industry’s confidence in separation protocols. When the most authoritative laboratory in the sector pauses to reassess a long-held assumption, the implications ripple far beyond a single test result. To understand why this moment feels so destabilising, it is worth revisiting how the industry arrived here. The rise of lab grown diamonds forced gemmology to evolve at speed. Early synthetics were relatively easy to identify, often displaying obvious metallic inclusions or irregular growth patterns. As production techniques improved, identification became more complex, pushing laboratories to invest heavily in photoluminescence spectroscopy, DiamondView imaging and advanced trace element analysis. Over time, a multi-layered system emerged, combining screening devices with confirmatory laboratory testing. Confidence grew not because any single test was perfect, but because the system as a whole was resilient.

When Tools Become Shortcuts

UV afterglow became one of the many tools in this layered approach. It was never intended to function in isolation, yet in practice it often did, particularly at the commercial level. Traders, manufacturers and retailers came to rely on fast screening decisions, trusting that the underlying science was settled. The reappearance of ambiguity exposes a structural weakness. When knowledge becomes operational shorthand, nuance is lost. From a geological perspective, the idea that natural diamonds could exhibit prolonged afterglow is not entirely implausible. Natural diamonds form under extraordinarily varied conditions over billions of years. Their impurity profiles are shaped by pressure, temperature, mantle chemistry and subsequent geological history. As analytical tools become more sensitive, behaviours once considered anomalies begin to look more like outliers that were simply invisible before. In this sense, the current moment reflects not a failure of science, but its progression. Better tools reveal greater complexity.

Commercial Stakes for Natural Diamonds

However, the commercial consequences of this complexity are significant. The natural diamond sector has invested heavily in differentiation, positioning itself as geologically rare, emotionally authentic and fundamentally distinct from lab grown alternatives. That positioning relies on trust, not only in narrative but in verification. Any suggestion that natural diamonds could be mistaken for synthetics, even temporarily, threatens to blur a boundary that the market has worked hard to reinforce.

Implications for the Lab Grown Market

For lab grown diamonds, the implications are equally complex. On one hand, the discovery undermines the assumption that certain reactions are uniquely synthetic, which could reduce stigma attached to specific optical behaviours. On the other hand, it risks intensifying scrutiny, leading to more conservative classification thresholds and potentially longer testing times. In a market that competes heavily on price, speed and scalability, increased friction is not welcome.

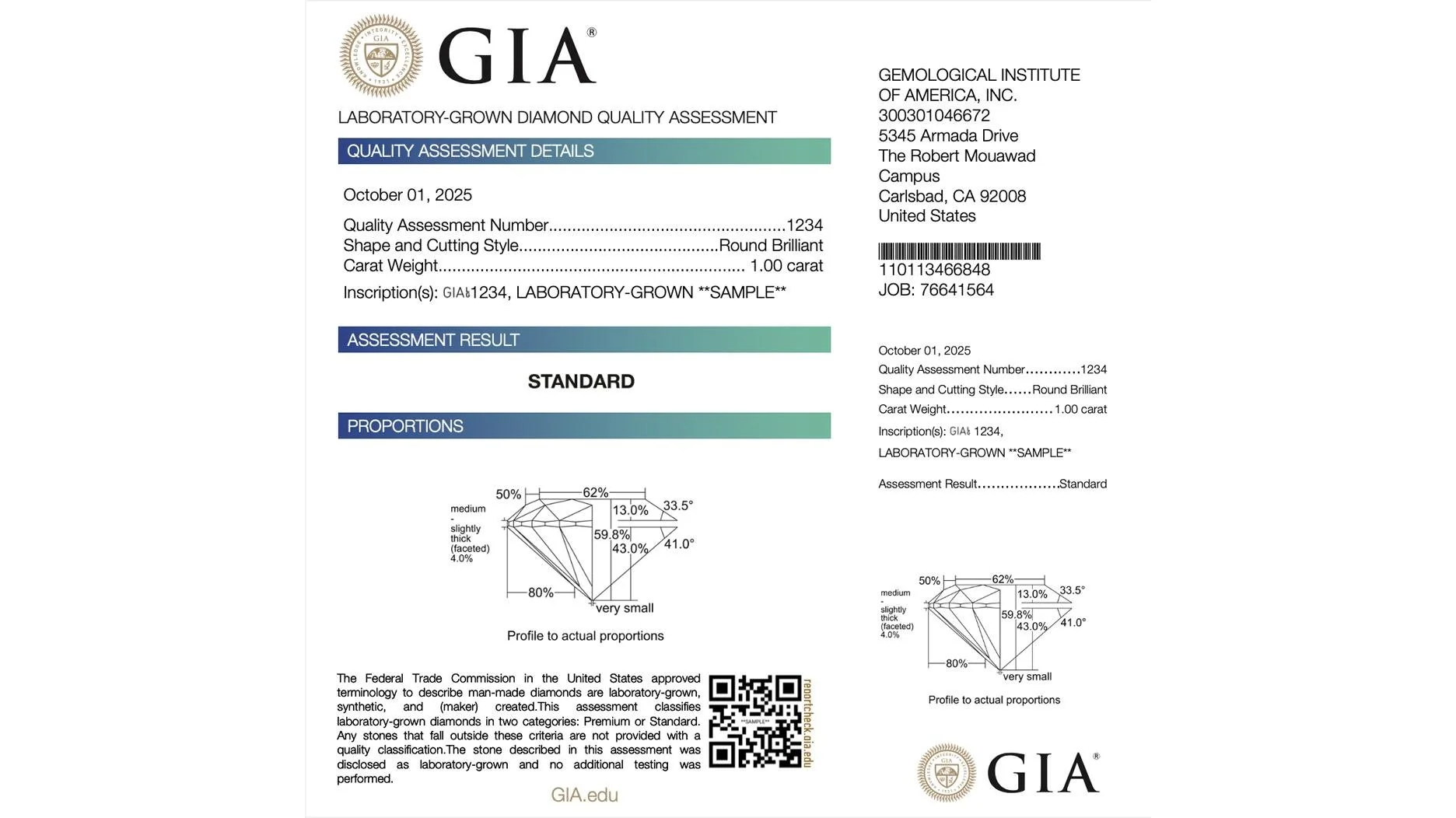

The role of gemmological laboratories now comes sharply into focus. Institutions like GIA, HRD and IGI are no longer simply arbiters of origin. They are custodians of market stability. Their methodologies shape insurance policies, auction catalogues, resale values and consumer confidence. A recalibration of testing protocols, however scientifically justified, must be communicated with exceptional clarity. Silence breeds speculation, and speculation erodes trust.

Is Disclosure Enough?

There is also a broader philosophical question at play. The industry has often spoken about disclosure as the ultimate solution. If every diamond is correctly identified and transparently disclosed, does it matter if certain physical behaviours overlap? In theory, perhaps not. In practice, markets do not operate on theory alone. Perceived risk affects pricing, liquidity and desirability. Even the suggestion that identification is becoming more complex can influence buyer behaviour, particularly at the high end, where rarity and certainty command premiums. Auction houses are especially exposed. The secondary market depends heavily on laboratory reports, sometimes decades after a stone was first certified. If certain characteristics once considered definitive are reclassified as ambiguous, historic stones may attract renewed scrutiny. This does not imply misrepresentation, but it does introduce uncertainty, and uncertainty is corrosive to value.

Complexity Is Not a Crisis

It would be premature to frame this moment as a crisis. The diamonds in question are not evidence that natural and lab grown stones are indistinguishable. Rather, they demonstrate that the boundary is more scientifically nuanced than previously understood. The danger lies not in complexity itself, but in the industry’s tendency to oversimplify complex science for commercial convenience.If there is a lesson to be drawn, it is that gemmology is not static. The diamond sector often speaks in absolutes, natural versus synthetic, rare versus replicable, permanent versus manufactured. Yet the material reality of diamonds resists such binaries. As detection technology evolves, so too must the language and assumptions that surround it.

Beyond Square One

In this sense, the question is not whether we are starting over, but whether we are finally willing to accept that the finish line never existed. Distinguishing natural from lab grown diamonds was never a problem to be solved once and for all. It is an ongoing process, shaped by innovation on both sides of the equation. Growth technologies improve, detection tools respond, and the cycle continues.

For professionals across the value chain, from miners to jewellers, the path forward requires intellectual humility. Relying on a single indicator, however reliable it once seemed, is no longer sufficient. Education, layered testing and transparent communication must take precedence over shortcuts. For consumers, this moment may ultimately strengthen confidence, provided the industry resists defensiveness and embraces clarity.